Shipping is a critical component of downstream supply chains, transporting commodities and finished goods valued at over USD20 trillion in 2023.

A strategically important waterway, the Suez Canal (constructed in 1869), reduces travel distances meaningfully. The canal connects the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea with approximately 10% of global seaborne trade transiting the Suez Canal and hence the Red Sea.

Over the last few months, tensions in the Middle East have forced trade flow diversions to avoid the Red Sea. This has resulted in expanded tonne miles, increasing asset utilisation rates and has driven up charter rates and dividend yields.

Overview

Whilst Hayfin does not have vessels within its fleet which are scheduled to transit the Red Sea, and we retain the ability in our contracts to reject any request to trade these waters, we expect the current market dynamics of expanding tonne miles and elevated asset utilisation rates to be persistent forces over the medium to longer term.

By exploring the history, geography, and commercial impacts we can better understand real time developments and current and ongoing shift in market dynamics.

Over the last few months, tensions in the Middle East have forced trade flow diversions to avoid the Red Sea expanding tonne miles, increasing asset utilisation rates, and driving up charter rates and dividend yields.

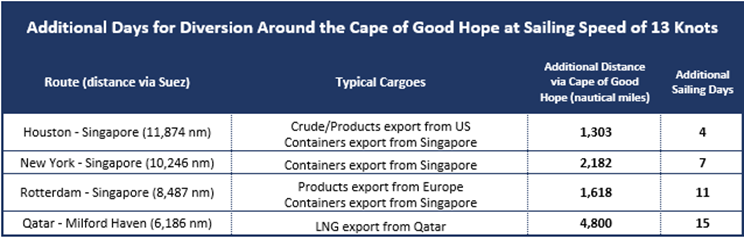

The table below illustrates increased sailing distances and voyage lengths for certain key routes.

At a sailing speed of 13 knots, diversions around the Cape of Good Hope can add up to 15 days in voyage duration, having a knock-on effect on charter rates, insurance premiums and fuel pricing/logistics.

- ‘War risk’ insurance premiums for Red Sea transits have risen by up to 10x.

- Availability of low sulphur fuel oil (‘LSFO’) at key bunkering hubs is a delicate balance; since mid-December 2023 pricing of LSFO in Durban, South Africa has increased 4.0x versus Rotterdam LSFO pricing.

Another consequence of recent disruption is that the proportion of Chinese owned ships transiting the Red Sea has increased significantly i.e. it is ‘western’ ships that are diverting around the Cape of Good Hope, further illustrating the impact of geopolitics in the conflict.

Geography

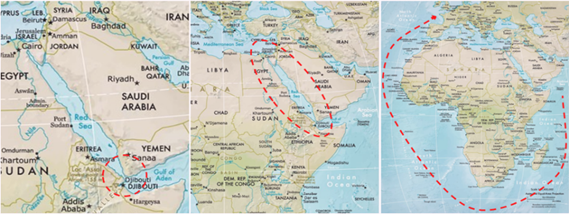

- Situated between the Arabian Peninsula and East Africa, the Red Sea provides access to Israel’s only port, Eliat, via the Gulf of Aqaba. At the southern end of the Red Sea lies the Bab-el- Mandeb Strait, bordered to the east by Yemen, and both Eritrea and Djibouti to the west.

- At its narrowest point, the Bab-el Mandeb Strait is just 21 miles wide, which is a similar width to the English Channel or approximately 20% of the distance between Florida and Cuba.

- Beyond the Red Sea, lies the Gulf of Aden, bordered by Yemen to the north and Somalia to the south.

Since the hijacking by Houthi militia of the Car Carrier Galaxy Leader (a vessel with links to Israel) on 19th November 2023 in a military operation involving the landing of heavily armed assailants aboard the vessel by helicopter, there have been around 30 attacks against ships transiting through the Red Sea. After what seemed to be an initial focus on vessels with links to Israel or simply calling at Israeli ports, the attacks have seemingly become increasingly sporadic and arbitrary, mostly against ships with no particular nexus to Israel.

As a result of these attacks, the United Nations Security Council has adopted Resolution 272 demanding the Houthis end their attacks and noting “the right of Member States, in accordance with international law, to defend their vessels from attacks.” Consequently, the US and its allies launched Operation Prosperity Guardian, deploying significant naval assets to the region, and launching a series of strikes against land-based targets in Yemen. In retaliation to these actions, the Houthis have shifted focus, attacking ships sailing in the Gulf of Aden off Yemen’s southern coast. This included a missile strike against the Gibraltar Eagle, a Bulk Carrier controlled by US- based Eagle Bulk Shipping, when it was located 90 miles southeast of Aden.

Commercial Impact

The threat posed by these attacks has forced diversions to avoid the Red Sea. Several shipping companies have publicly stated that they will no longer transit the Red Sea.

- It is estimated that since mid-December 2023, Containership arrivals in the Gulf of Arden have fallen 90%, Car Carriers 94%, Tankers 46%, Gas Carriers 86%, and Dry Bulk, least affected, at a 24% decline.

- These diversions also increase the complexity of voyage planning, particularly in terms of sourcing the availability of bunkers (ship fuel). Bunkering is available in South Africa, but supply is limited, and fuel costs are high. For example, as of 18 th January 2024, a metric tonne of LSFO cost USD537 in Rotterdam, USD600 in Singapore, and USD780 in Cape Town.

- The increase in tonne miles has in turn impacted the cost of freight. At the end of September 2023, the Shanghai Composite Containerised Freight Index (the barometer of the seaborne cost of shipping containers from China to global markets) settled at a post-pandemic low of 886.9. By the middle of November, it had risen to 1,000, and has since doubled, reaching 2,206 on 12th January 2024. In product tanker trades, we have seen evidence that spot rates for voyages that would usually pass through the Suez Canal have risen 30-50% since mid-December. Spot rates for long range and medium range product tankers have risen 33% and 29% respectively in the week ending 19th January 2024 alone.

- The southern reaches of the Red Sea have, for some time, been designated a “High Risk Area” for insurance purposes requiring ship owners to pay additional premium for transits. On 18th December 2023, the Joint War Committee at Lloyd’s of London extended the High-Risk Area from 15 degrees to 18 degrees, broadly to encompass the entire lower third of the Red Sea. War risk premiums for Red Sea transits have risen 10x from 0.075% – 0.125% in early December, to 0.5% – 0.75% of the hull value.

- There is also a human impact upon crew members forced to sail in the Red Sea. The crew of both the Galaxy Leader and the St. Nikolas, comprising Ukrainian, Bulgarian, Filipino, Greek, and Mexican nationals are still being held hostage.

Conclusion

Supply chains operate with delicate equilibriums, and delays or disruption tend to increase pricing, benefiting ship owners but perpetuating commodity price inflation.

We have experienced these dynamics several times recently with the trade disruptions during the Covid 19 period, the Suez Canal blockage in 2021 due to the Ever Given, the drought implications in the Panama Canal and the profound impact of shifting energy flows due to the Russia/Ukraine conflict.

The current market dynamics are no different. Since Q4 we have seen increases in the Shanghai Composite Containerised Freight Index by 2.5x. In the same period spot rates on certain refined product tanker trades have increased by up to 50%.

Unlike fixed physical infrastructure, m aritime assets are liquid and dynamic. This is evidenced by shifting trade flows away from the Red Sea and the Suez Canal, instead taking the long route around the Cape of Good Hope as those with interest in ships seek to protect their crews, assets, and cargoes. This drives up freight costs and tightens shipping markets due to increased tonne mile demand.

Persistent trade flow disruptions and expanding ton miles are expected to remain a more permanent feature within supply chains and these market dynamics, on top of healthy long term demand fundamentals, are expected to exacerbate supply/demand imbalances and could likely lead to sharper or longer periods of elevated rates and higher asset yields. When considering these fundamentals against portfolio construction considerations, staggered duration charter contracts across a diversified hard asset base as well as “index-linked” or profit share structures are well positioned to capture these gains and dividend streams.

The kind of interruption to maritime trade that we are currently seeing in the Red Sea has a wide range of ramifications. This includes, first and foremost, the crew members and civilians endangered or otherwise directly impacted by the instability in the region. It also affects consumers and businesses in the form of higher commodity prices and freight costs. But for shipowners and other maritime investors, supply chain disruption can drive up rates and therefore boost yields. This combination of favourable pricing dynamics and a more challenging operating environment looks set to remain a feature of the shipping industry in the medium to long term – layered on top of a longstanding and fundamental supply -demand imbalance that is the primary driver of investor interest in the shipping market.